The Romantic Lyric Structure

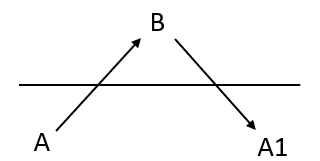

The answer lies in the structure of the Romantic lyric. Jack Stillinger identified that the lyrical poetry of Keats’s time followed a structure as identified in this diagram:

The horizontal line represents the boundary between the real world (below) and the imaginary, or ideal, world (above). The ideal world is placed above because it is considered by the poet to be a higher reality. At the beginning of the poem the speaker starts in their reality (A) before performing an imaginary flight (B) and finally coming back to reality slightly changed (A1) (Stillinger, 2009, pp. 6 – 7).

We can see how Keats’s Ode follows this pattern: starting in a melancholy state, the speaker is enchanted by the song of the nightingale but is finally brought back to reality and views life differently.

Additionally, Frodo starts in Rivendell (A) before visualising and feeling what the Elves are singing about (B). Here is the full description:

At first the beauty of the melodies and of the interwoven words in elven-tongues, even though he understood them little, held him in a spell, as soon as he began to attend to them. Almost it seemed that the words took shape, and visions of far lands and bright things that he had never yet imagined opened out before him; and the firelit hall became like a golden mist above seas of foam that sighed upon the margins of the world. Then the enchantment became more and more dreamlike, until he felt that an endless river of swelling gold and silver was flowing over him, too multitudinous for its pattern to be comprehended; it became part of the throbbing air about him, and it drenched and drowned him. Swiftly he sank under its shining weight into a deep realm of sleep.

There he wandered long in a dream of music that turned into running water, and then suddenly into a voice. (Tolkien, 2007, p. 233).

When Frodo returns to reality (A1), he does not wish to discuss any news of the Shire or the ‘dark shadows and perils that encompassed them’, rather ‘fair things they had seen in the world together’.

By extension, it could even be said that the overall structure of The Lord of the Rings builds on the loose structure of the Romantic lyric. Frodo leaves the Shire (A: reality) and journeys wide in Middle-earth (B: imaginary, ideal) where he learns that the outside world is not what he originally thought. Once the One Ring is destroyed, he returns to the Shire but is irreversibly changed (A1). He cannot settle back into his old life the way his friends do. Whereas the traditional Romantic lyric would conclude here, Tolkien goes further. He has Frodo leave the Shire and the world of Middle-earth for a metaphorical after-life in Valinor. This can be labelled C as it recognises that to return to reality with the intention of continuing one’s life is not achievable as you could be left traumatised by your experience. Frodo therefore does not seek the ideal but a new experience where he is removed from reality and the imaginary altogether.

What stands out between Keats’s Ode and Frodo’s experience is how the imaginative flights are triggered. The speaker of the Ode will not be ‘charioted by Bacchus and his pards, / But on the viewless wings of Poesy’ (Keats, 1988, p. 347; ll. 32 – 33). Poetry is the method whereby the Romantic poet accessed the ideal and it is the nightingale within the Ode that enchants the speaker to take flight. The particular emphasis on the sensual element further intensifies our experience. ‘Viewless’ implies that we are moved by poetry not through sight but through sound; the sound of the nightingale, the sound of the poem being read aloud is what unlocks our ability to fly.

“The sound of the poem being read aloud is what unlocks our ability to fly.”

Tolkien works in much the same way. It is the artistry of the Elves and its oral performance that initiates Frodo’s enchantment. The words transform in a diversely sensual way that immerses Frodo into a vivid dream where he experiences what is being sung, rather than just picturing it. In this way, Tolkien is employing the device known as synaesthesia.